High-performance computing (HPC) clusters come in a variety of shapes and sizes, depending on the scale of the problems you’re working on, the number of different people using the cluster, and what kinds of resources they need to use.

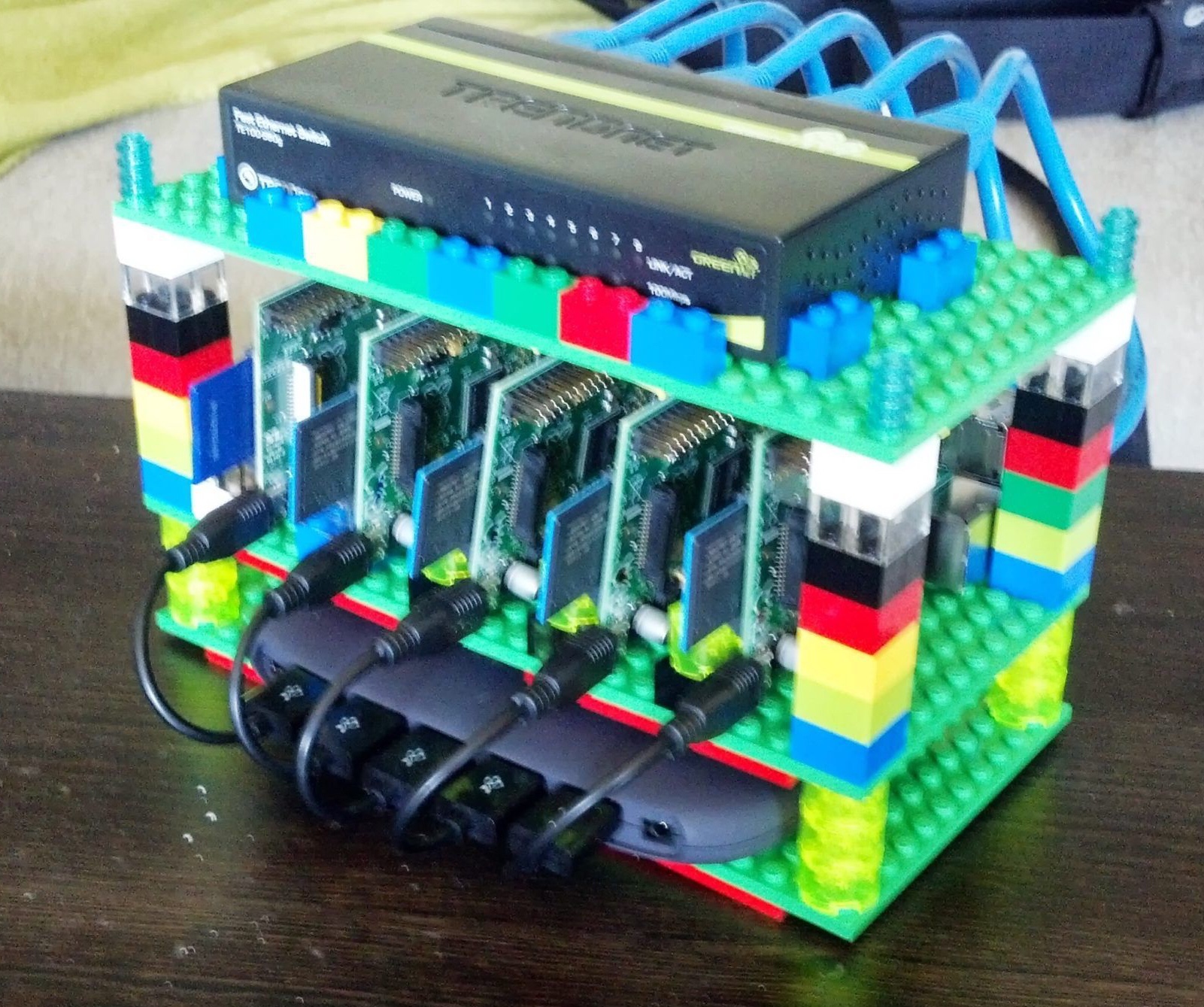

However, it’s often not clear what kinds of differences separate the kind of cluster you might build for your small research team:

From the kind of cluster that might serve a large laboratory with many different researchers:

There are lots of differences between a supercomputer and my toy Raspberry Pi cluster, but also a lot in common. From a management perspective, a big part of the difference is how many different specialized node types you might find in the larger system.

Just a note: in this post I’m assuming we’re talking about compute clusters of the type that might be used to run simulations or data analysis jobs. This probably won’t help if you’re designing a database cluster, a Kubernetes cluster to serve a web infrastructure, etc.

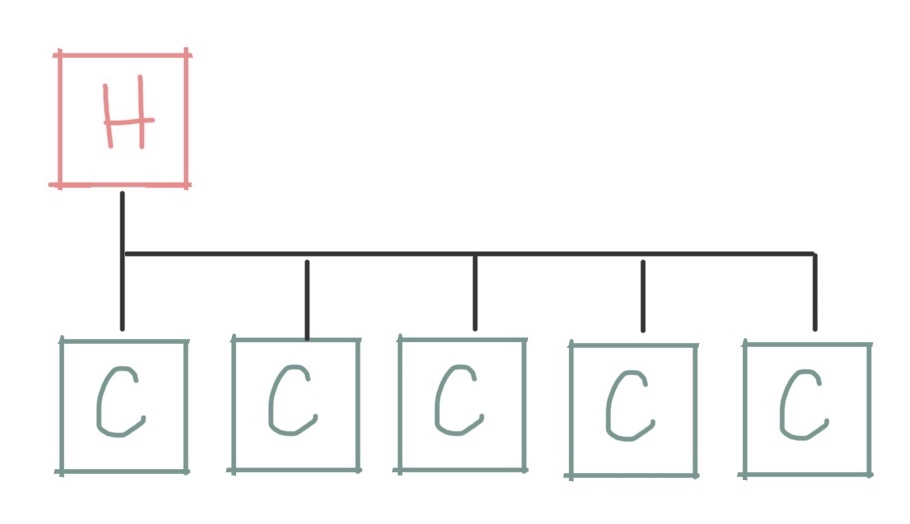

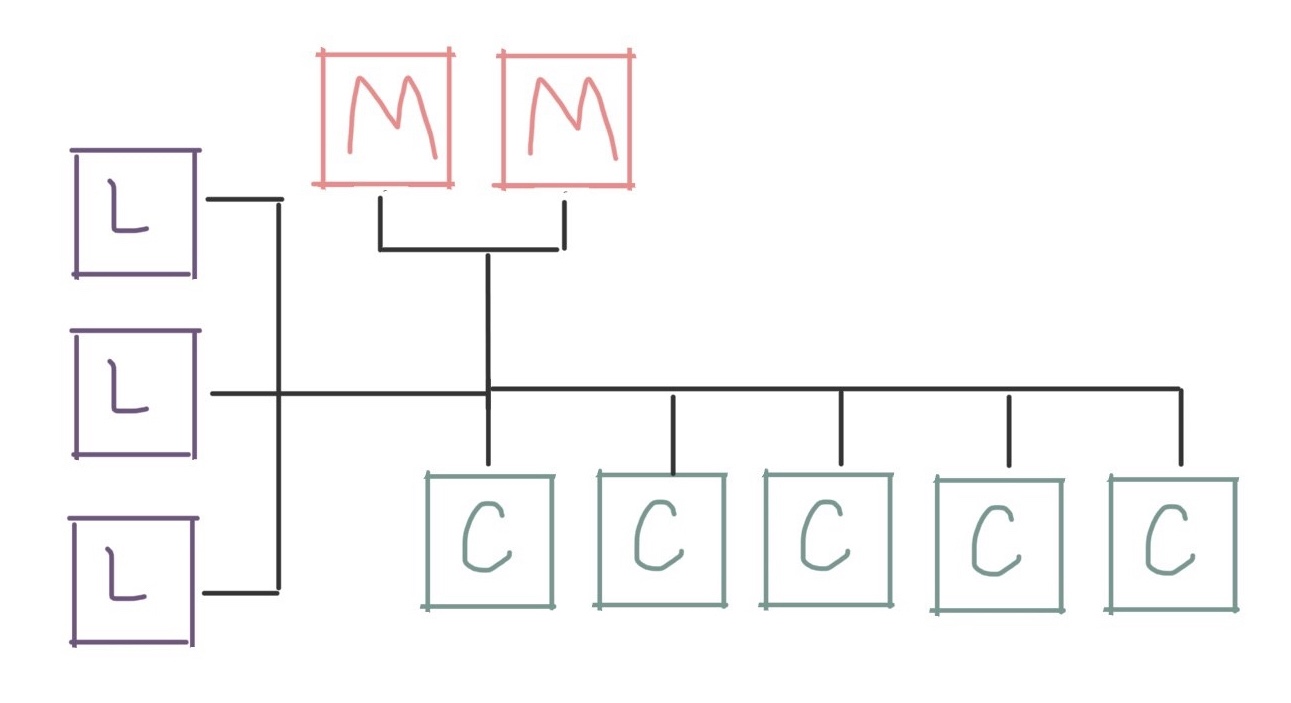

Let’s start with one of the simplest ways you can build a cluster: a collection of compute nodes, all connected to a network, with a single “head node” that coordinates work between them:

With this design, the head node performs most of the functions that coordinate work or provide shared services on the cluster. The compute nodes are then free for the actual compute jobs on the cluster, like simulating the weather or analyzing telescope data!

Some of the shared services that most clusters provide from the head node include:

- Running a job scheduler that accepts requests from the users and queues them up to run on the compute nodes

- Exporting a shared filesystem to the other machines, so they can all access the same storage space

- Accepting user logins so that the people who want to run on the cluster have an access point to the cluster

- Acting as a management node that the cluster sysadmins can use to help maintain the rest of the cluster

This kind of design can scale remarkably well, and it’s probably the most common kind of cluster out there. But at some point, you might find that the head node is doing too much, and you need to split its functions across multiple machines.

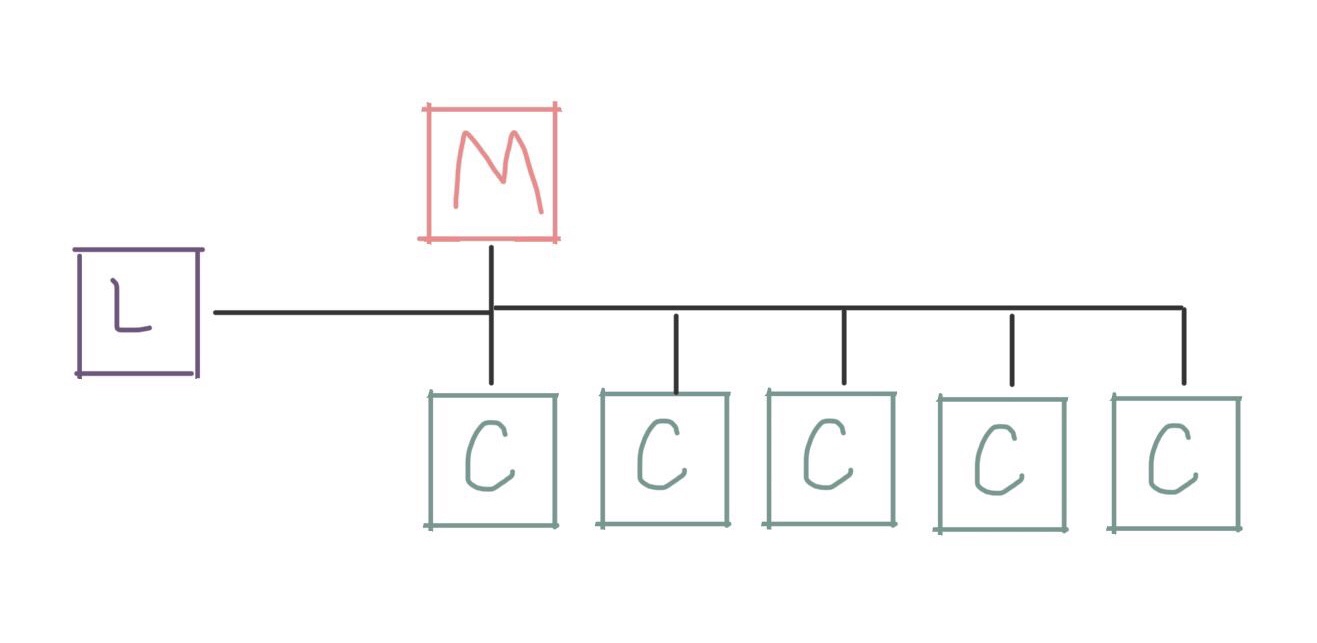

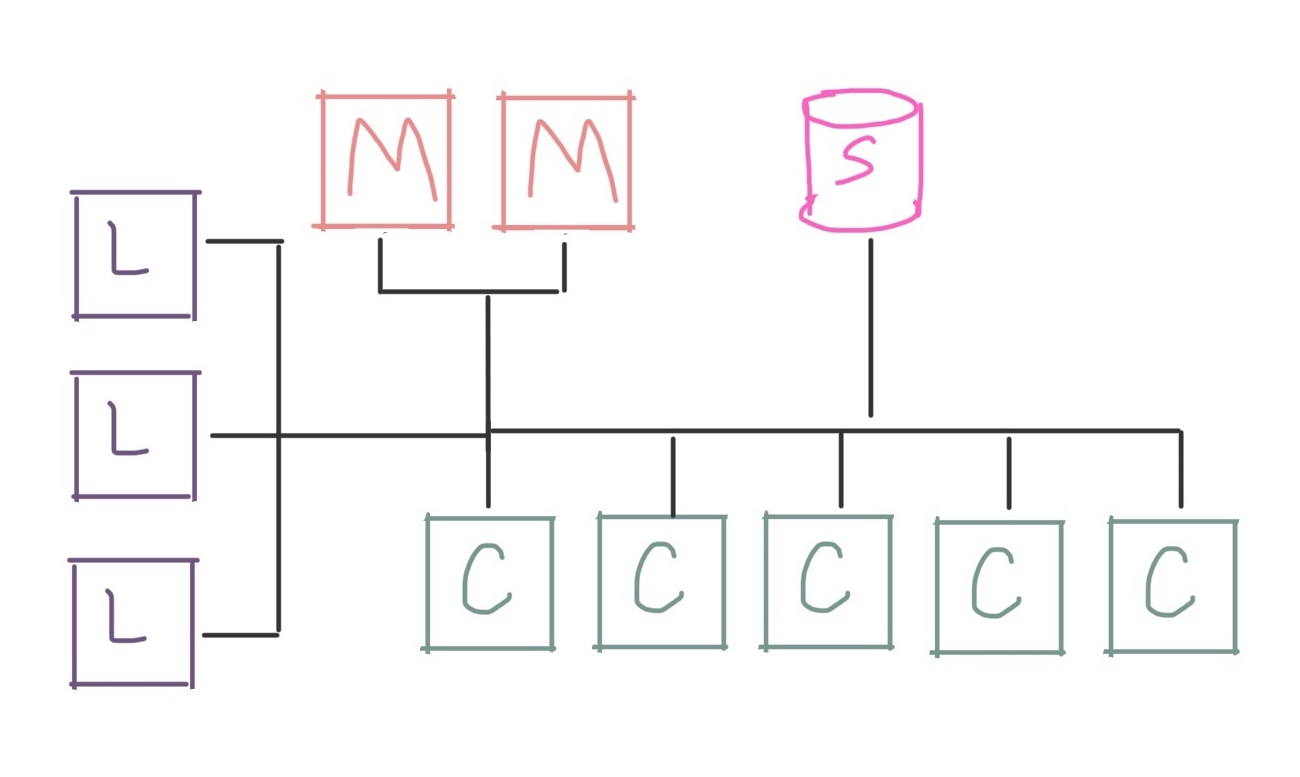

The first thing you’ll often see is moving user logins onto their own dedicated login node:

All the other functions are still on the head node (which is often explicitly called a management node at this point). But by moving user logins to their own node, it becomes easier to do maintenance or make changes to the larger system without disturbing your users.

(It also means that if your users accidentally crash the login node, they’re less likely to take down all those shared services on the management node…)

If you have lots of users, you can also easily add more login nodes! These scale pretty well because the shared services are all still on the management node, but your users get more interactive nodes for their development work

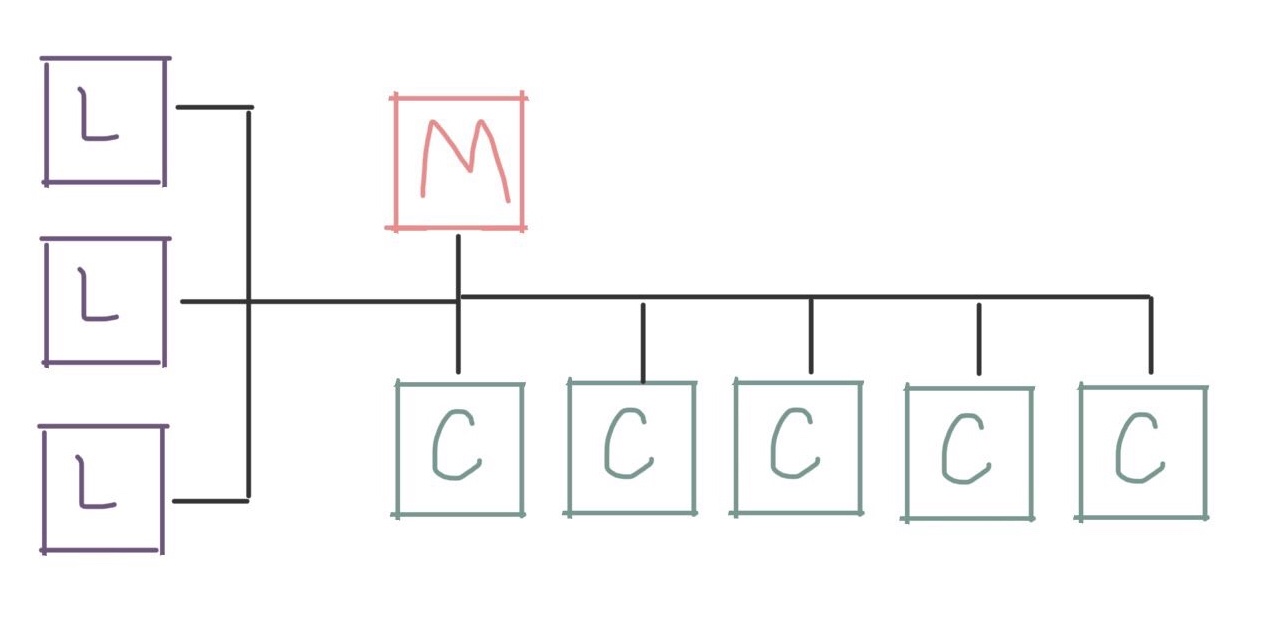

At this point, you might also set up a second management node in order to provide redundancy or failover in case your primary management node fails:

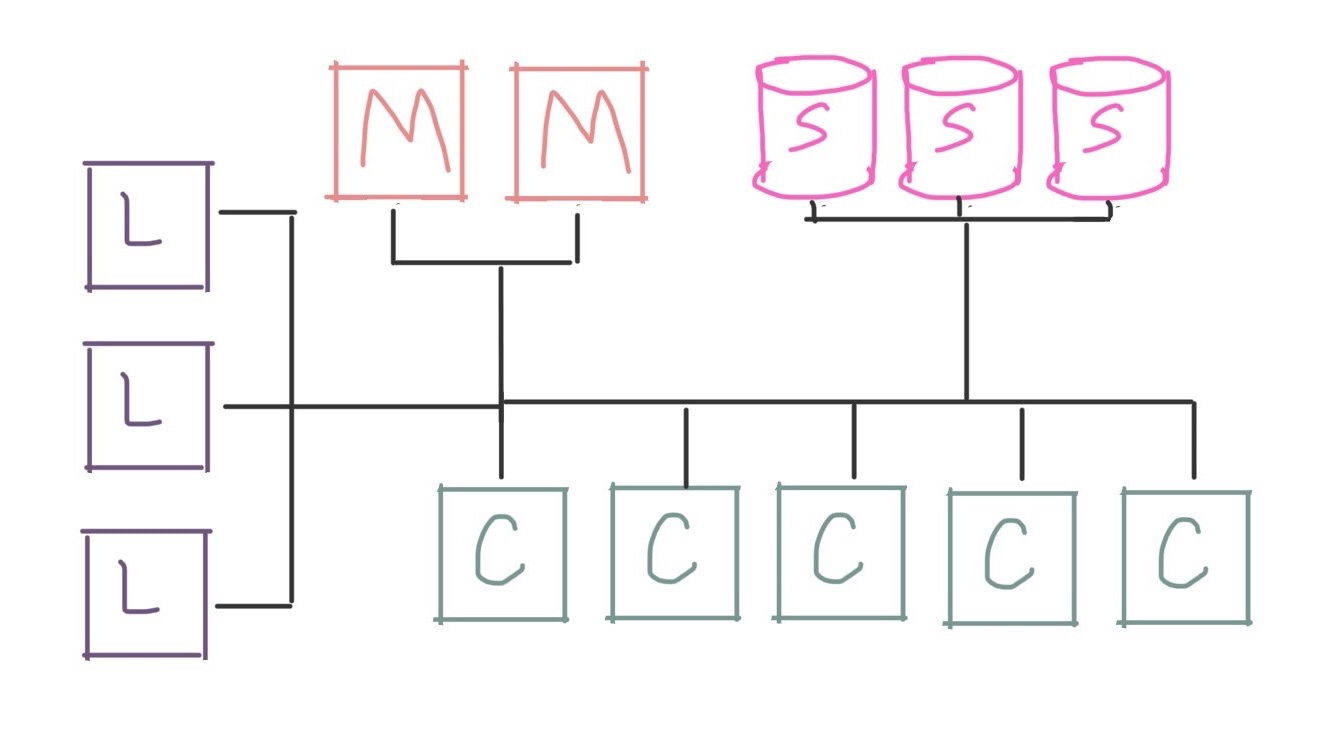

At this point we have a lot of compute nodes, redundant management nodes, and a nice collection of login nodes for the users to use for their work. What else might we need as we scale up?

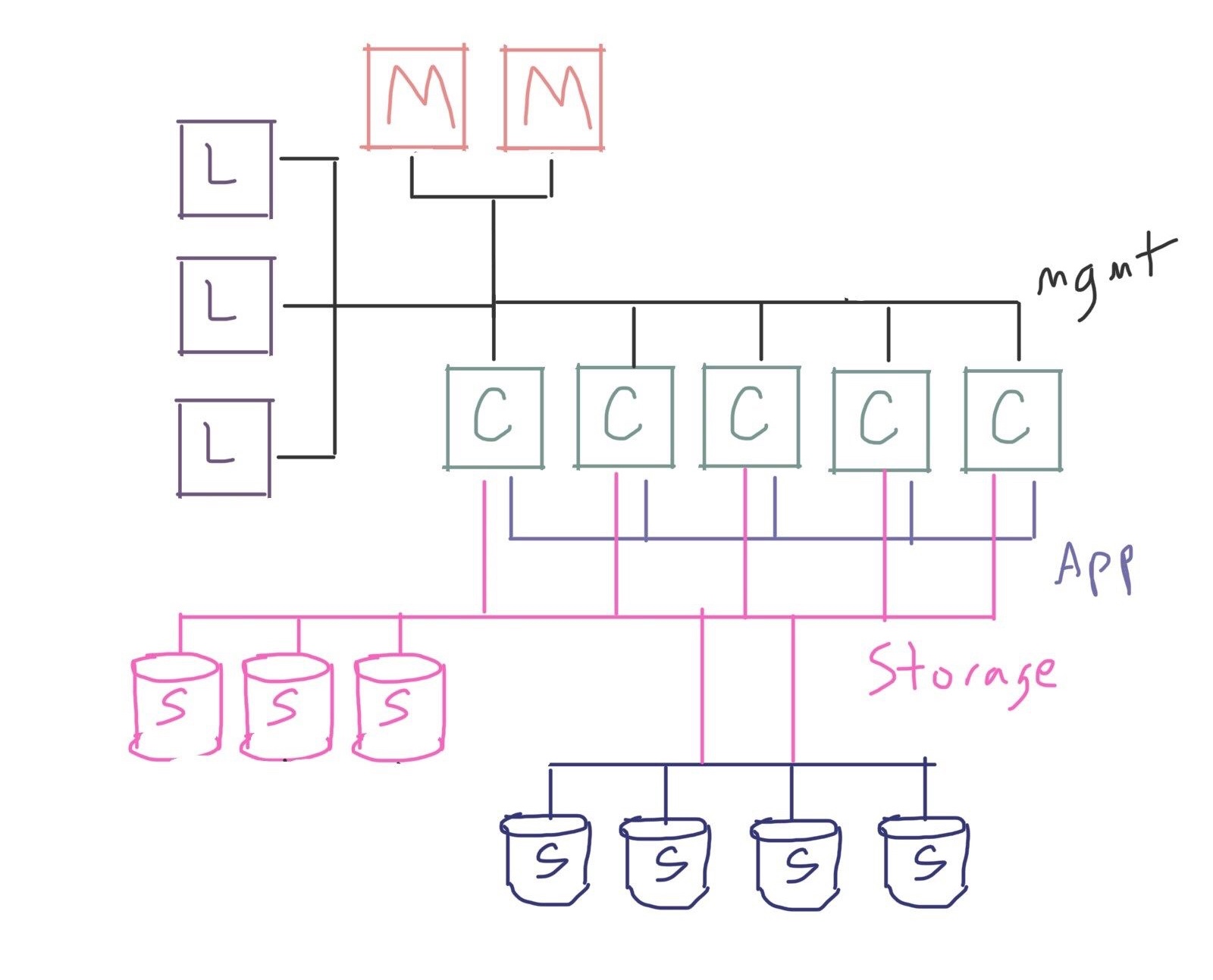

Well, for one thing, the shared filesystem is still on the management node. We might want to split it off onto its own machine to provide better performance:

Or if we want to scale our performance higher than a single storage server can provide, we might want to use a distributed filesystem like Lustre, BeeGFS, or GPFS and provide a whole tier of dedicated storage machines:

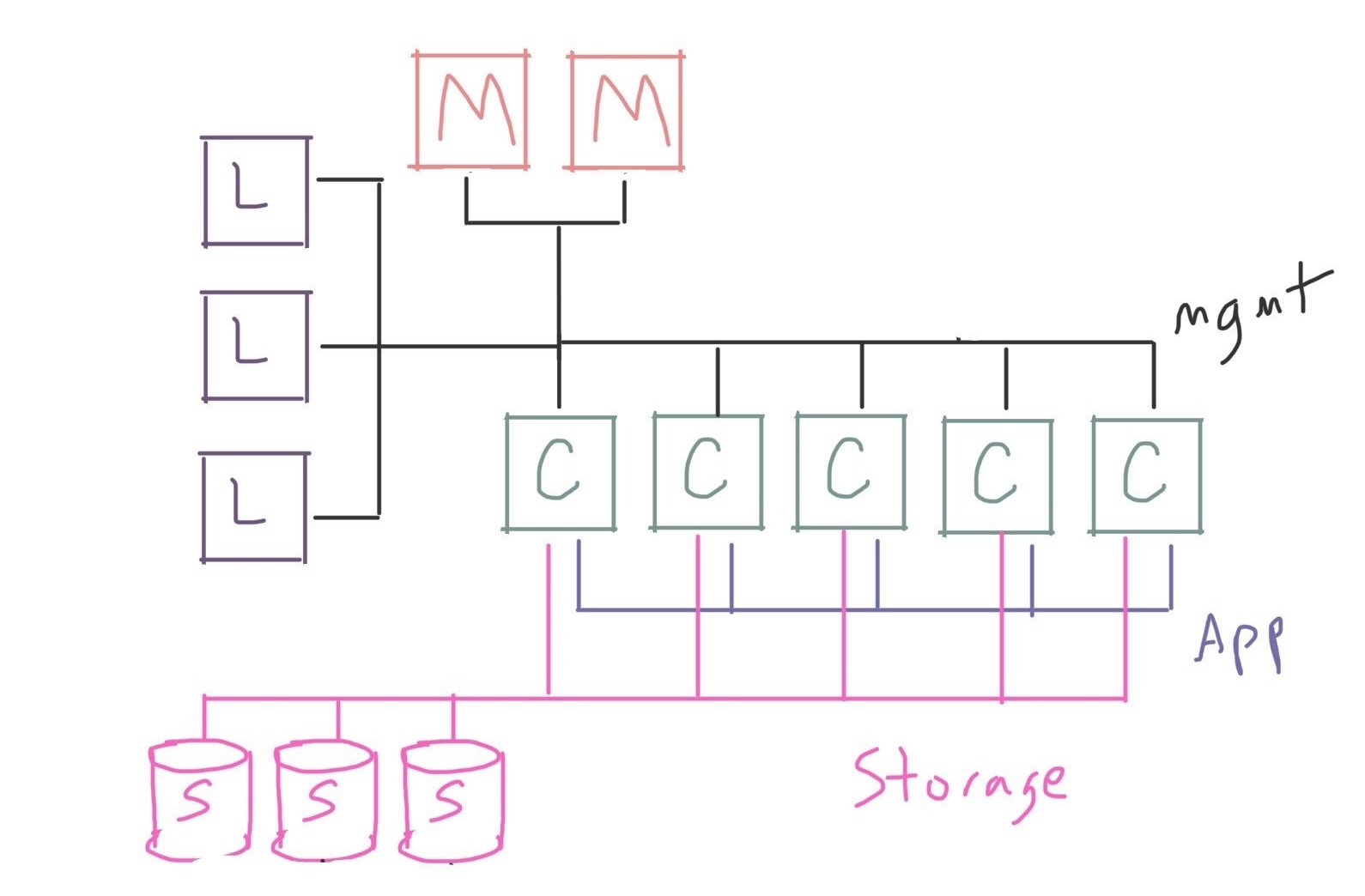

You might also notice that we’re using the same network for everything! Communication between compute nodes, access to storage, and management services are all competing to send messages over the same network. This could be a problem if, for example, the application wants to simultaneously read lots of data from storage and exchange messages with neighboring compute nodes.

At this point we may want to split these different types of traffic onto their own networks:

Depending on how much you need to optimize (or how much you want to spend!), you may have several different networks connecting all the machines in the cluster, separated by function. You may have dedicated networks for functions like:

- High-speed network (or application network): This is a dedicated network for user applications to communicate between compute nodes, and is often built using specialized hardware like Infiniband or a vendor-proprietary technology. This is especially important if you use technologies like MPI in your applications, which rely heavily on inter-node communication.

- Storage network: This is a dedicated network for access to storage. If you rely on especially fast network storage, you might use Infiniband or another very fast network here too.

- Management network: This is often the “everything else” network, used for job scheduling, SSH, and other miscellaneous traffic. This is often a less-performant network, using 1Gb or 10Gb Ethernet, because we expect the heavier usage to be on the application or storage networks.

- Out-of-band management network: Many datacenter environments have methods for managing individual servers outside their operating systems, such as accessing the baseboard management controllers. However, this kind of access can be a security risk, and it’s often put on its own network to restrict access.

All these different networks may be on their own hardware, for the best performance; or they may be virtual networks (VLANs) sharing the same physical connections.

Once you get past this point, there are many different ways to continue splitting off or adding special-purpose functions, but these are less common outside of very large sites.

For example, you may have multiple independent storage systems you want to access:

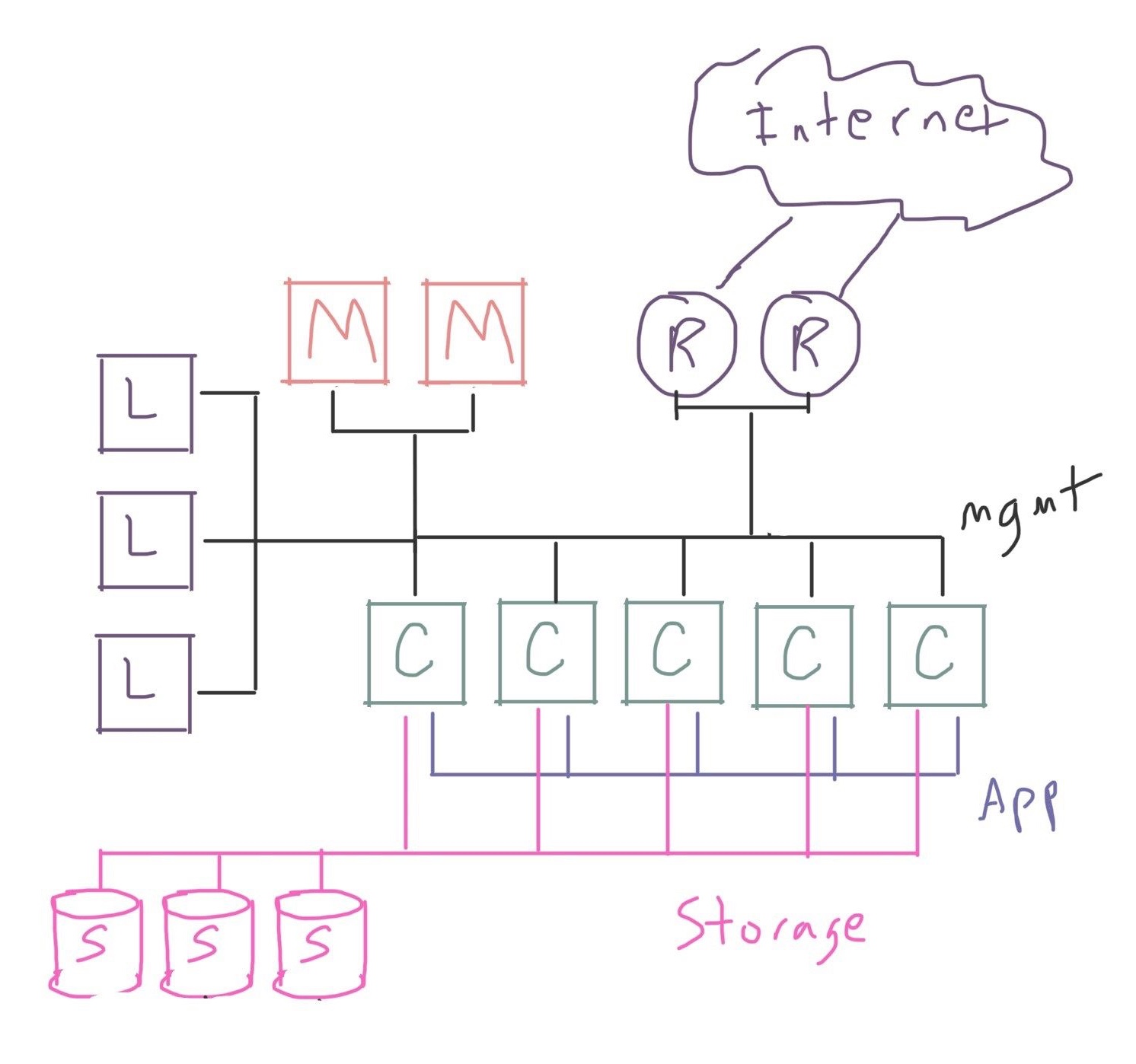

Or your cluster may depend on fast access to an external resource, and you want to attach a dedicated tier of network routers:

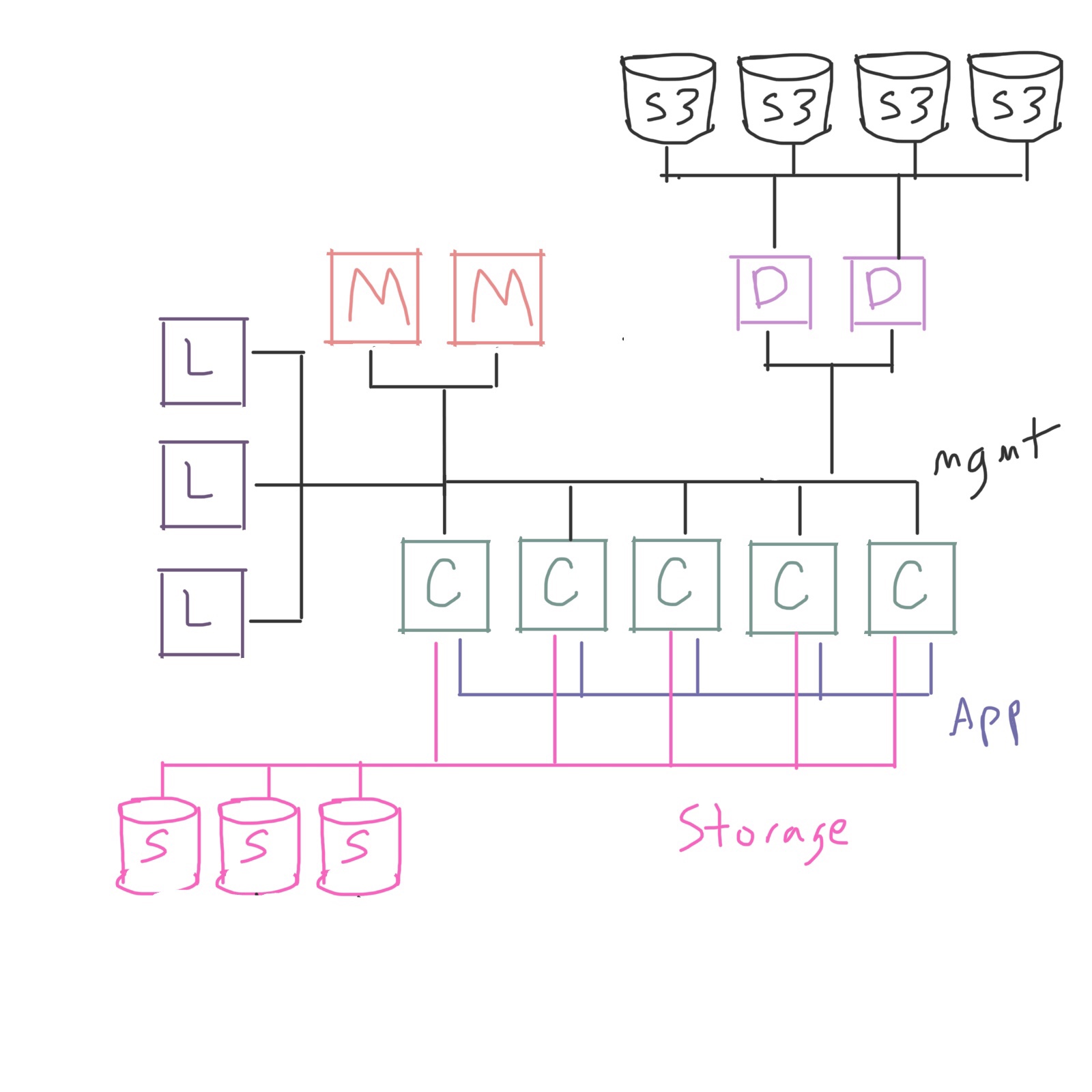

Or you may even have some slower tier of storage that you need to move data in and out of, such as S3 or a tape system, and build a set of dedicated machines for data movement:

In other words, you can add as much complexity as you like! ? Or, as much as your users and workloads require. Very complex environments serving many researchers may have many different tiers of dedicated machines, for data movement, network routing, managing software licenses, and more. But not every environment will need this type of complexity.

In all cases, the general strategy is the same: if your work is being bottlenecked by some you special-purpose function, you may consider moving that work to dedicated machines to get better performance.

This needs to be balanced, though, against the costs of doing so, in money, power, rack space, or other constraints. Frequently, there’s a trade-off between adding special-purpose machines and adding more compute machines, and your users might prefer to just have more compute!